Beethoven and Biblical Theology

Using the Third Symphony to Reflect on What is of First Importance

“We use musical metaphors all the time when we talk about the Scriptures, without even thinking about it,” say Alastair Roberts and Andrew Wilson.

We might describe the Bible as a symphony or a love song.

We might refer to the opening of Genesis as an overture or to Revelation as a finale.

We might talk about the story being composed or perhaps orchestrated by God, with themes and rhythms and echoes running through it, all building to a crescendo.

If we are handling some of the difficult sections, we might say that there is a clash here or a discordant note there,

but that there is always, ultimately, a harmony within the Word of God, and therefore that we can expect things to resolve. (Roberts and Wilson, Echoes of Exodus, 21. Emphasis and formatting added.)

Composers use a musical form called “Theme and Variations.” As you might guess, the compositions begin by clearly stating a “theme” and then vary that theme (the “variations”). Classical music affectionados love the “theme and variation” format, including Bach's Goldberg Variations, Mozart's variations on "Twinkle, Twinkle,” and Elgar's Enigma Variations.

The identical order of these pieces provides a predictable structure for the listener. This predictability enables listeners to follow along with the music and expect the next section of a song.

But when composers depart from predictability, they create a dramatic impact. And so do biblical authors. Let’s consider Beethoven so we can better understand the Bible.

Beethoven’s Third Symphony

A very dramatic departure from predictability happens in the opening movement of Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

The piece begins with two orchestral . . . stabs.

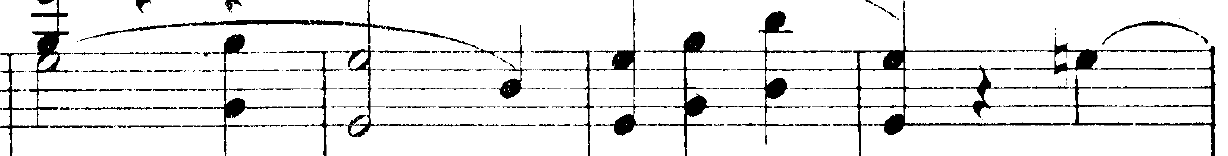

And then we expect to hear the theme. The cellos (bass clef) play this:

If you don’t read music, let me explain. First, our theme begins with eight very basic (almost childlike) notes, tracing the most basic chord (tonic in Eb). But then the melody takes a . . . downward twist, descending to a C#, concluding the childlike opening with a sinister haunting.

Second, we soon hear the theme again, about eight measures later. This time, the theme is in the woodwinds (treble clef).

Here, our childlike theme, instead of descending to a C#, ascends—first up to E natural and then to F. (Trust me; it’s after a page turn.) Instead of a sinister descent, Beethoven gives us an anxious ascent.

Musically, we do not know how the theme ends. And over the next twelve minutes of his symphony, Beethoven keeps the conclusion of this theme a secret. Beethoven leaves us guessing: does the theme go down? or go up? Sinister haunting or anxious ascent?

Music and Theology

Perhaps my love for and familiarity with music prejudices me, but I believe that music is one of the best ways to understand the Bible. Roberts and Wilson agree with me.

“A musical reading of Scripture does more justice to the way Scripture actually works than, say, a pictorial reading, or even a dramatic reading.

Plays are linear: this happens, then that happens, and although the past obviously shapes the present and future, it never comes back.

Pictures are representative: this is a picture, an image, a copy, a shadow, a silhouette of that.

Scriptural typology is more like a piece of music: familiar themes like temple, kingdom, exodus, judgment, and sacrifice keep recurring, but always slightly differently” (Echoes of Exodus, 26–27; emphasis and formatting added).

While Beethoven is a brilliant composer, the God of the Bible is a compositional genius without peer.

Scripture’s Main Theme: Jesus Christ

My ears find similarities between Beethoven’s Third Symphony and the biblical story of redemption. The Bible doesn’t use the predictable “theme and variations” model. The biblical authors use Beethoven’s model (or Beethoven uses their model, or however you’d like to say it).

The Old Testament authors write Christ’s theme with fragmented motifs; they never state him clearly.

Sometimes, the theme descends and falls into sinister haunting. A blessed garden-keeper falls when he eats forbidden fruit. The rescued ark-builder falls to the ground, drunk and naked. The first high priest falls on his knees to worship some gold he calved. A triumphant prophet falls in the wilderness because he struck a rock. A temple-building king takes foreign wives and an entire nation falls in exile.

Other times, the theme rises into anxiety. An anxious father rises early in the morning to raise his knife over his only son. A trusting mother rises to place her infant baby in a waterproof basket. A Moabite widow rises, leaving her homeland to cling to her new God.

The Bible waits until the person and work of Jesus Christ to state its theme clearly.

Beethoven waits until the coda section to state his theme unambiguously. Heard first from a lonely French Horn, the entire orchestra soon joins the theme.

Here, finally, our theme neither descends into sinister haunting nor rises in ascending anxiety. The final note repeats with conviction, victory, and triumph. By withholding the clear statement until the end, Beethoven (and God!) create the sense of “At last!”

The Value of Minor Chords and Dark Scenes

We rarely enjoy the darker scenes of the biblical stories or the darker scenes of our lives. God’s people are not clueless optimists, but biblical realists who recognize evil for what it is. God warns, “Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter!” (Isaiah 5:20).

And yet Christians also must trust a God who allows darkness in our story.

Although Beethoven was a remarkable composer, only a few people love his Eighth Symphony. It is a work remembered more for it brevity than for its brilliance. In keeping the symphony short, Beethoven omits the darker sections people usually associate with his genius. Without darker sections (what Beethoven scholar Scott Burnham calls a “psychological abyss”), critics describe the Eighth Symphony as having “ultimately lighter weight” (Beethoven Hero, 50).

Christians trust God. He has written dark passages for our lives, but we know he has walked through the darkest passages himself. Thus, in the words of the hymn by Richard Baxter, “Christ leads me through no darker doors than he went through before.”

Let us follow God’s leading through the passages of our lives, following him through the sinister, haunting descents as well as through anxiety-inducing ascents.

And may we remember the destination of this leading. In the words of Gregory the Great, that Christ is leading us “to that blessed city of everlasting day, where all are one in heart and mind, where there is safety and eternal peace, happiness and delight.”

See you there!

I am so glad that you found this issue of my newsletter. I plan on writing ten issues in ten weeks (this is #8) and then evaluate how it’s going. If you’re reading this paragraph, that means you finished this issue. That means a lot to me. Click the “like” button to let me know you got all the way to the bottom!

I recently appeared on a podcast with Churchfront Worship Leaders talking about Best Worship Resources. Check it out!

Are you coming to the T4G conference? I’m appearing on a panel with my friends Mike Cosper and Dr. Matt Boswell to talk about corporate worship. Click here for details.

Interested in studying worship at the seminary level? It just got a lot easier. Check out our Online Masters Degrees (MA in Worship Leadership and MDiv in Worship Leadership).

Southern Seminary has made it easy (and cheap!) to visit our beautiful campus. Preview Day is April 22. :)

Thanks you! Again, if you’re not subscribed, consider joining us. That sort of feedback will inform my decision to continue writing this newsletter or not.

Great writing, Matthew. I am afraid I will be singing, “oh my word, it’s Beethoven’s third,” in my head all day.

Love the analogies!