Welcome to issue 11 of my newsletter! A special welcome if you are just joining us, and an extra special welcome if you’ve already subscribed.

Since this is a newsletter about worship, let me note that this is the first week of Lent. For a historical overview of why some Christians observe Lent and others don’t, consider reading my essay, “Lent It Go.”

That essay is lengthy, but it contains a unique anecdote about St. Nicholas’s pelvis (footnote 15).

On to this week’s issue!

The previous issue of our newsletter (did you miss it? Find it here) discussed a common consensus among evangelical worship thinkers of the 1950s and 60s. Here’s the consensus: something was missing from evangelical worship services.

The consensus disappeared when evangelicals discussed what was missing and how to fix it. This issue of our newsletter discusses one idea about what was missing: historical roots.

During the 1960s and 70s, some evangelicals were convinced that evangelical worship services had become detached from their historical roots. Evangelical worship services were poor, and from this perspective those poor worship services ought to be enriched by drawing upon historical roots.

Perhaps the most obvious candidate for a leader and spokesperson for this movement is Robert Webber (1933–2007).

Webber received a broad education from all sorts of schools, including fundamentalist (bachelor’s degree from Bob Jones University), Episcopal (a divinity degree from the Reformed Episcopal Seminary), Reformed (master's degree from Covenant Theological Seminary), and Lutheran (the doctoral degree from Concordia Seminary) institutions. Dr. Webber served as a professor of Theology, first at Wheaton College and then at Northern Seminary.

Webber was a keen observer of Protestantism and a prolific author who wrote on a variety of topics, though his most important books discussed worship. Perhaps the single book that encapsulates his philosophy best is Ancient Future Worship, while the breadth of his thinking (and community!) can be seen in his seven-volume collection, The Complete Library of Christian Worship.

In these books and many others, Webber argued that the church needed to embrace the past and utilize the liturgical riches that the Christian tradition offered to support of today’s church.

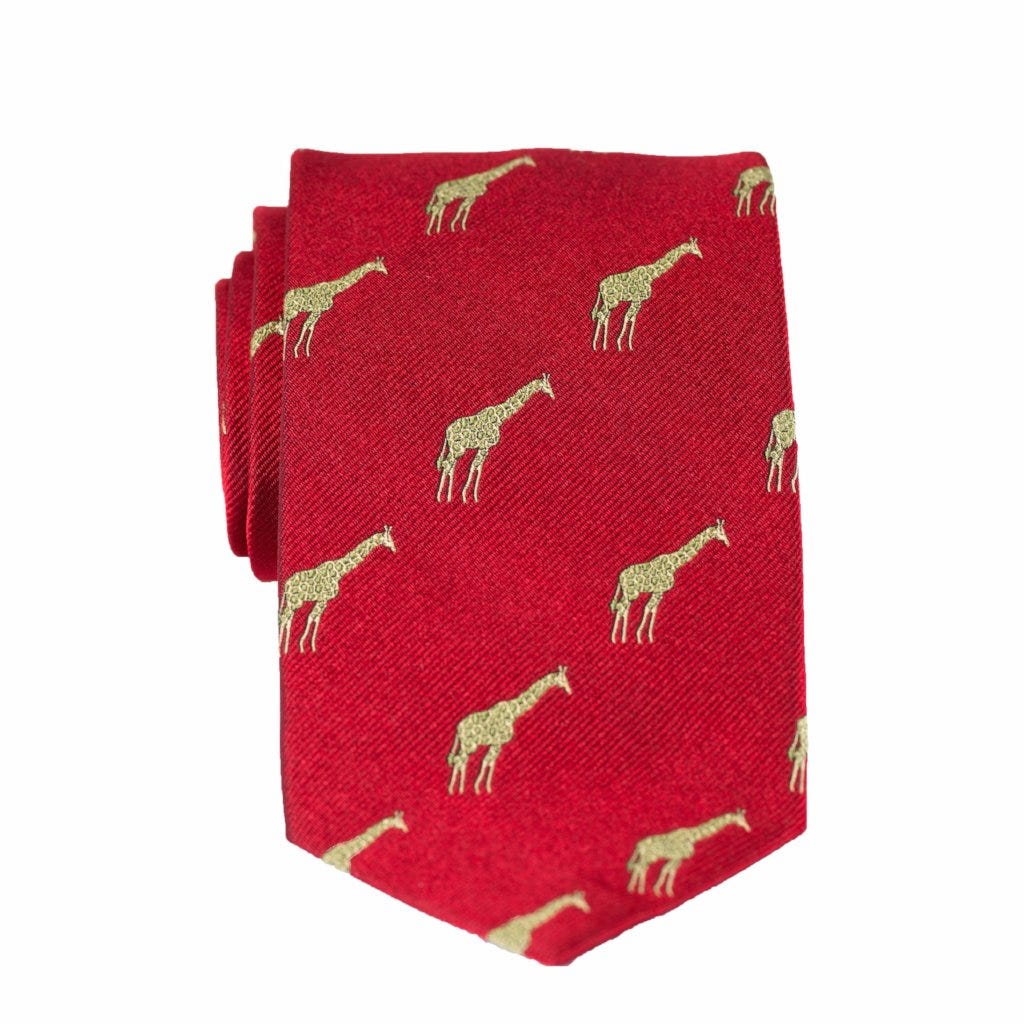

As an illustration of that, let me tell you about one of my favorite ties—the giraffe tie.

When my grandfather passed away, my aunt sent me to his closet to choose some ties that I might want to wear. Men’s style is always changing—sometimes ties skew skinnier, sometimes wider—but a classic tie is always in style. When I saw a classically shaped tie with giraffes, I immediately grabbed it. (My grandmother adored giraffes, which often adorned her earrings or necklace.)

This illustrates the direction that Robert Webber and other like-minded worship reformers championed for Protestant churches. They wanted contemporary churches to “look in the closets” of previous generations and bring out some liturgical treasures that are always in style. No one argued this logic better than the Lord Jesus, who taught that “every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a master of a house, who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old” (Matthew 13:52).

Many of the publications of the 1970’s and 80’s emphasized this perspective. Christians of this era read about the spiritual journeys of people like Thomas Howard and Peter E. Gillquist, introductions to classical spiritual disciplines from Dallas Willard and Richard Foster, and renewed Evangelical interest in the patristics from Donald Bloesch and Thomas Oden. This inspired some to draw upon historic liturgical expressions in a blend of evangelical, charismatic, and sacramental-liturgical expressions of Christian worship.

In 1977, a gathering labeled “National Conference of Evangelicals for Historic Christianity" met in Chicago (discussed in Christianity Today). After several days of discussion, they offered “The Chicago Call.” Concerning worship, they write

We decry the poverty of sacramental understanding among evangelicals. This is largely due to the loss of our continuity with the teaching of many of the Fathers and Reformers and results in the deterioration of sacramental life in our churches. Also, the failure to appreciate the sacramental nature of God’s activity in the world often leads us to disregard the sacredness of daily living.

Therefore we call evangelicals to awaken to the sacramental implications of creation and incarnation. For in these doctrines the historic church has affirmed that God’s activity is manifested in a material way. We need to recognize that the grace of God is mediated through faith by the operation of the Holy Spirit in a notable way in the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Here the church proclaims, celebrates and participates in the death and resurrection of Christ in such a way as to nourish her members throughout their lives in anticipation of the consummation of the kingdom. Also, we should remember our biblical designation as “living epistles,” for here the sacramental character of the Christian’s daily life is expressed.

Webber and others called for churches to fully participate in the table and the font (the Lord’s Supper and baptism), to regularly recite ancient creeds and historical confessions of faith, and to faithfully draw upon time-tested liturgical prayers. The quest for historical roots called evangelicals to mine the depths of our traditions (and even other traditions!).

Many readers of this newsletter know someone who grew up in a Baptist or evangelical church, but changed denominations to something more liturgical—Anglican, episcopal, even Roman Catholic. While I am a convinced (and happy!) low church Baptist, it is important to consider and understand the draw of these things.

Sometimes, the oldest part of a Baptist worship service is the sanctuary’s out-dated carpet. An evangelical who visits a liturgical church and hears the congregation reciting the Apostles’ Creed encounters a profound truth: “This is a faith that's older than me, a faith that’s been tested through time.”

This helps us understand the pull of liturgical advocates like Tish Harrison Warren and James K. A. Smith as well as the resurgence of books of prayers, like Every Moment Holy or Valley of Vision.

That can be encouraging, and, in its own ancient way, even strangely exciting.

Next week, we will discuss a second attempt that evangelicals advocated for in the Evangelical Quest for More—the Quest for Skills. We will discuss the church growth movement and its shaping influence on contemporary worship.

If you made it this far, thank you! Click the “LIKE” button to let me know you finished the article.

Instead of writing about hot topics in worship world (heaven knows there are plenty), I am trying to write longform, thoughtful investigations that triangulate the worship ecosystem and help worship planners navigate the influences that shape their services. I hope it is helpful.

Things I found helpful this week include

Ari Hoenig’s incredible drum solo: “You Can’t Play the Piano on Drums” (3 minutes).

“Is Congregational Singing Dead?” by Benjamin Crosby (10 minutes).

An author interview with Dr. Jim Hamilton on his new commentary on the Psalms (16 minutes).

And a new arrangement of “Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lamb?” by my friends at Boyce College.

“See” you next week!